057 – dBA vs. dBC

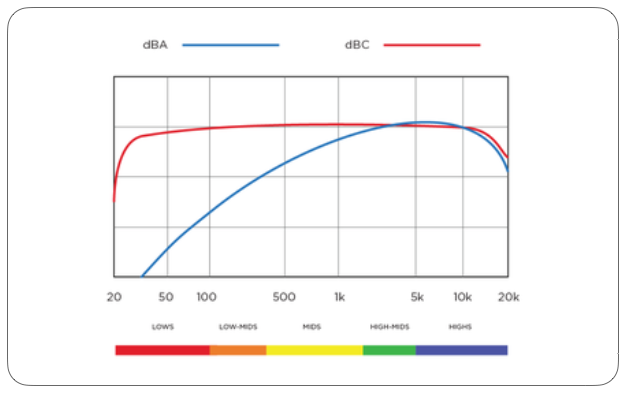

To understand the difference between dBA and dBC, we need to look at the frequency curves they use.

Written by Scott Adamson

One of the main concerns with live music is volume. Even music that's not necessarily supposed to be loud can still be painful in the high-mids, or too boomy in the low-mids, or just cranked to a higher volume than is appropriate. Of course, there are some artists that are meant to be loud, and when I’m on tour with someone like that they’ll request that I really push the mix.

However, some venues have strict decibel limits. A decibel meter tells you the SPL (sound pressure level, which is measured in decibels) and if I go above that volume I’ll be asked to turn down. And if I don't comply, the house engineer may do it themselves in the system processing. It’s never a good idea to let it get that far.

This can be frustrating. For example, two iconic outdoor Los Angeles venues have strict decibel limits - the Greek Theater and the Hollywood Bowl. I've done shows at both and been a little bummed out when I want to turn it up but am already at the decibel limit. But it's part of the job, and if the mixes are good enough they’ll still sound nice and full at a lower volume.

Even if I’m not mixing super loudly, I still find it helpful to know the SPL. Especially when I’ve been working a lot, my ears get tired, which can affect my perspective. Using a decibel meter is a good way to keep tabs on my mix to make sure I’m in the right ballpark. I talk more about this in my latest YouTube video:

Decibel readings for music are typically done with two different measurements: dBa and dBc. We also call these A-weighted and C-weighted decibels. They both measure SPL but use different frequency curves to weight the reading.

More often than not, you'll see A-weighted decibel limits. In theory, this is supposed to be a realistic representation of human hearing since our ears are more sensitive to midrange frequencies. That’s why most people use it as standard.

However, A-weighted decibel readings only really work at lower volumes and don't take into account the loud low-end frequencies we have at a lot of shows. C-weighted measurements include more of the low frequencies. When we get up to loud volumes, this is actually closer to how we hear it.

Get real-world live sound mixing tips straight to your inbox.

In almost all situations where someone is measuring SPL at a show, they’ll use A-weighting, even though it’s technically less accurate. But this is a good thing when you’re mixing with a decibel limit! A-weighting can be more forgiving, and if you have a show with a lot of low end, you’ll start to push the dBc readings much higher.

Of course, every artist is different and every engineer has their own style of mixing. But for me, if I’m trying to hit the sweet spot with volume, I’ll mix rock/pop bands around 100 dBa, or between 105 and 110 dBc. This is definitely loud! But I find it’s the volume where really good mixes can shine (and bad/harsh mixes get painful to listen to).